The Rocky Emotional Aftermath of My Gym Climbing Accident

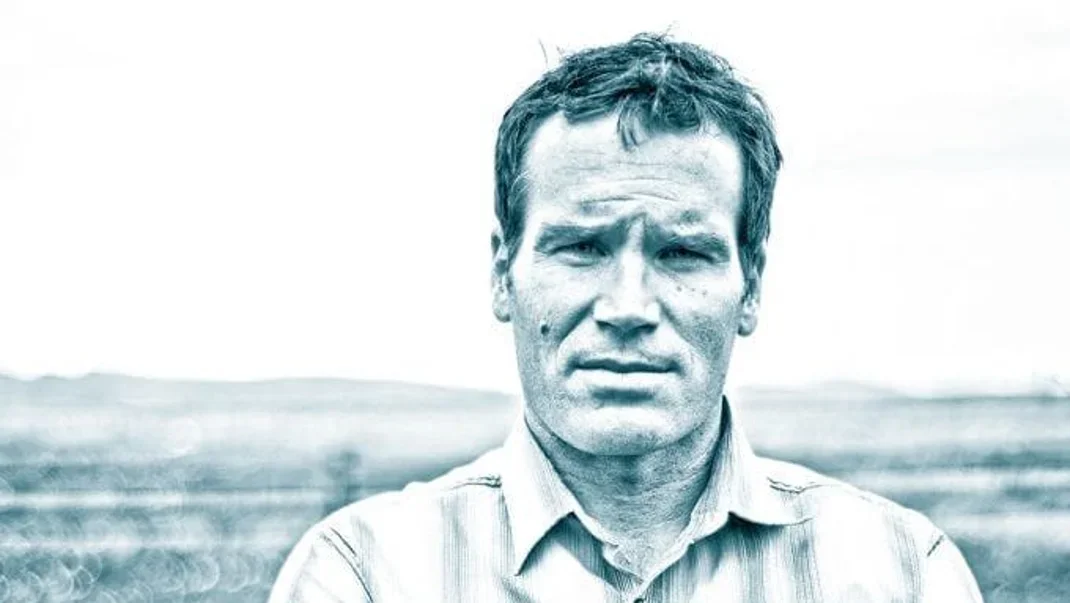

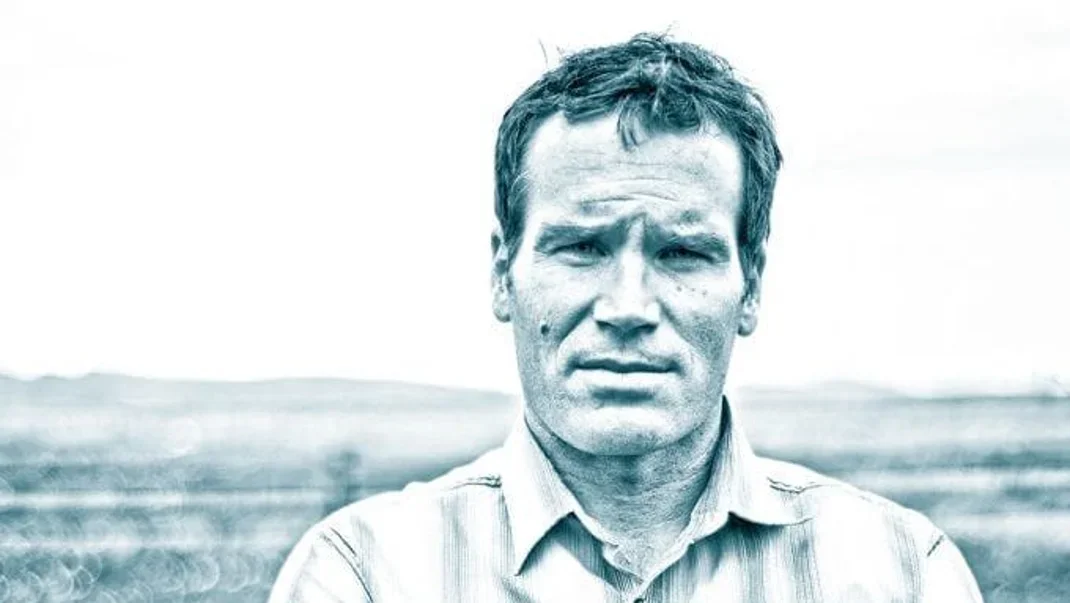

A stranger he met at the gym dropped him to the ground. In the aftermath, the author had to relearn how to climb—and to trust.

The post The Rocky Emotional Aftermath of My Gym Climbing Accident appeared first on Climbing.

I worked through the final roof moves, then reached to pull up rope to clip the anchors. I looked down at the stranger who was belaying me and my heart pounded. Beginning to panic, I released the slack I had pulled up and yelled, “Take! Take! Take!” He stood motionless, staring blankly, imploring for a translation. He had backed 20 feet away from the wall, and looked at me and then at his hands, and the Grigri between them, with confusion. He did nothing to bring in the ominous arc of limp rope between himself and my first quickdraw. If I hadn’t spent the morning feverishly running laps on different auto-belays throughout the gym, I might have had the strength to save myself. Instead my arms shook violently as if I was holding on to a jackhammer. I made a quick, crude calculation, thinking that the Grigri would automatically catch me just before I hit the ground. I let go. I hit the floor violently. On impact my back gave way, my ribs ricocheted off my pelvis, and my head bounced, clapping silent the hum of the gym. On the padded blue floor, I listened as a ringing din grew in my head, with urgent voices yelling for help. I felt hands stabilizing my head and hips, and someone softly taking hold of my hand. The stranger hovered just out of sight. I couldn’t understand what he was saying. Then a friend of mine who worked at the gym told him to back away.

Earlier that year, while I walked with a friend in the August heat below Settlers’ Park, a distraught woman flagged us down, telling us that help was needed on a nearby trail. We raced toward a panicked kid. In an amphitheater of rock, just above the bustle of my hometown of Boulder, Colorado, I just stood and stared. The kid paced back and forth, asking, “Is he dead?” I mistakenly thought that I was going to be a first responder, but there was nothing to be done. The man’s skin had gone blue, starkly contrasting with the bright red cone of blood suspended from his nose and mouth. The flies had already found him. I visualized him crawling there to die and thought maybe he’d fallen from the rocks above, or that maybe he’d been attacked. I thought of his family; the last thoughts he might have had. Something cold and soulless settled within me like dark ash. There was nothing we could do for him.

The paramedics carried me out over the February snow, and in the ambulance my left big toe felt as if someone had just cut it with a scalpel. I couldn’t see it because my neck was braced and my forehead was taped to the board beneath me. I thought of my wife, Monica. I wanted to call her and reassure her that I would be OK. I wanted to see her face. I wanted to hold my children’s hands. The paramedics kept asking if I wanted anything for the pain, but I felt that without the drugs I could keep an eye on my toe, and on the hollow nauseating feeling in my back. A cold hand had crept under the back of my skull.

I kept wiggling my toes and fingers, and tried to remember the paramedics’ names. I was in pain. I was afraid. And that same sick, helpless feeling I had staring at the dead man months before crept back in.

In the emergency room the doctors and nurses kept repeating that I was lucky to be alive. I probably would have been paralyzed had it not been for the thick padding on the gym floor. My wife arrived at the hospital between the CAT scan and the MRI, and when I saw her I finally gave in to the fear I’d kept rigidly in check. We were told that I had fractured my back at T12, broken a transverse process, herniated three discs, and, “rung [my] bell pretty good.” I would need to spend a few nights upstairs to get checked out by a neurologist. The doctors also needed to figure out the sensation in my toe to see if the nerves connected to T12 were in any way affected, which could result in lifelong incontinence and impotence. Months later I realized that I’d also cracked a molar and ripped up the cartilage in both knees.

The first night in the hospital I woke up three times soaked through with sweat, my heart thundering and my chest heaving. Every time I dozed off, the suddenness of the fall returned. I clicked for another drip of morphine. I clicked it all night long, staring at the clock, waiting for the next 15-minute window when the machine would release the clear liquid through the line and into my arm. The ticking and breathing of the machinery above me kept me from sleep, as did the haunting image of the swarthy stranger who had approached me, looking for a climbing partner. I saw the thick shadow of his beard, his quiet watery eyes, and heard the way words formed in the back of his mouth, half swallowed.

I didn’t feel any particular ill will toward him—mistakes happen—but he hadn’t called. He hadn’t come to the hospital. He hadn’t contacted the gym to see if I was OK. For all I knew, once I was back-boarded and loaded onto the ambulance, and the clamor of the accident subsided, he shoved his gear in his pack and vanished. As I lay there ruminating, the injustice began to eat away at me. It did not seem right that my family should suffer the cost of his mistake. Also, it sure as shit felt like a hit-and-run. I became hell-bent on tracking him down.

I dozed off and woke to my phone buzzing with a message from Monica:

hi babe. thought abt you all night. barely slept. I miss you so much. r u up? woke up missing u. love u. 3:44am

As I lay there immobilized and hooked up to a tangle of wires, I tried to make sense of my mistake. I never climbed with strangers. I only trusted a handful of old friends as my partners. Of course, there were exceptions—I once hooked up with Jimmy Chin to climb Half Dome. But primarily, I climbed with people I felt deeply connected to, otherwise preferring to climb alone. But I had just returned from the Deep South with my students to study the civil-rights movement and had been struck by the warmth with which we were received. There had been hugs and handshakes like those from family. I came home intent on opening myself up more to others. So I had accepted the stranger’s offer to climb. Now I couldn’t even remember his name.

Before becoming a teacher, I worked as the Outward Bound Wilderness safety and training director, looking critically at incidents to determine the root causes, then implement policies and procedures to avoid future accidents. So I knew what had happened. I had no misconceptions. I had mis-assessed. He answered yes to all of my questions. Told me he knew how to belay. But there were signs. He had “forgotten” his belay device. His harness was too new. He was short-roping me at some of the clips, and each time I looked down he was standing farther from the wall. I remembered that when I let go from the top of the climb, there was a brief hiccup in the fall, which must’ve been the Grigri auto-locking before releasing. He must have thought the lever on the Grigri was the brake, and so yarded on it to try and stop my fall.

By the time the light faded from my hospital-room window on the second day, our community had rallied. Friends from different sides of my life started overlapping at the edge of my bed. Without hesitation they had put the brakes on their lives in order to be with us. Their response made me feel ashamed by all the time I’d spent pursuing adventure or training to get stronger. It all seemed like a pathetic waste. I should have been showing up more for my friends. In that moment my tireless pursuit of climbing seemed so self-indulgent and devoid of meaning, and I was disgusted by my gluttony.

The second night the panic attacks continued. I couldn’t sleep without the fall returning. The doctors prescribed Xanax and my wife encouraged therapy. I thought of other falls I had taken. The reality of this fall, in a gym, no less, was harsh and irreverently defiant of my previous 20 years of climbing. Back in 1996 on El Capitan, a micro-cam levered out when I weighted my etriers, and immediately, with the flat pop of a gun, all of the brass nuts below it simultaneously blew out of the rock. A tiny RP—the width of a nickel—stopped my fall after 40 feet. Dangling unscathed, I was face to face with my belayer, nervously laughing and inhaling the acrid smell like gunpowder that engulfed our perch 2,000 feet up the Muir Wall.

Then while attempting a first clean ascent of Swoop Gimp in Zion in 1998, I ripped a hook from the soft sandstone and fell to within four inches of the ledge that would have rammed my hips up into my armpits. Not to mention the thousand-foot, 45-degree snow slope in the Olympic Mountains, where as a teenager I lost my footing. Without an ice axe, I slid while digging my fingers into the late-summer snow. I hit the black boulder field at a mad speed, and somersaulted through the air to land flat on my back—and my father’s external-frame pack. Stunned and helmet-less, I stared up at the blue August sky and inventoried my body, exhaling when I found nothing more than blood on my fingers, elbows and knees.

And then there were all of the moments that went right, but could have easily gone wrong. On Astroman in 2009 I found myself runout, pumped, and looking down at the last piece of gear far below and to my right. I knew if I fell I would drop 30 feet and then pendulum harshly to the right, dragging the rope across a sharp flake. If the rope cut, I would have fallen 700 feet into the manzanita bushes and talus. To escape my predicament I had to ease up onto a high tiny edge with my left toe, a move I could probably not reverse, while pulling on sloping edges with my fingers and then, what? Eventually I just plowed into the ugly heart of my fear, high-stepped, and shifted my weight up over my foot before spanning far to my right to regain the flake. My body barn-doored recklessly. I pulled back against the flake with sweaty hands, pasted my feet, and then gunned for the anchors.

After three days, when I could get out of bed, sit in a chair without throwing up, and shuffle to the bathroom, I was released and wheeled out of the hospital. My back brace, designed to create traction, pressed firmly into my sternum and pubic bone in the front and just above the break in the back. Before we returned home I demanded that Monica take me to see a personal-injury lawyer to sue the guy who had been belaying me. He had failed to call, visit or send any signal that he had done anything other than tuck his tail and run.

I could barely walk, but with my hand on my wife’s shoulder, shuffled through the lobby to meet with two lawyers, who assured us that we had a powerful case against the man who had dropped me. We just had to find him. So my wife and friends harassed the gym to get his information. After much effort we were given his name, Nir, an Israeli address, an international phone number, and a local cell number to a phone that rang and rang until a message mechanically stated, “This phone has not been set up for voicemail.”

In my absence, my two young daughters had decorated a bed for me in our family room, piling on it every pillow in the house, the book I’d been reading, my toothbrush and a stack of plastic bags because they had heard I’d been throwing up. With Monica’s help, I stiffly levered into the bed and lay rigid and exhausted, staring at the ceiling and inhaling the smell of our home. I hadn’t seen my girls yet. Monica didn’t want them to see me in the hospital like that. When a friend dropped them off, they came quietly in the door and I could see Stella, my 4-year-old, studying me, looking for something, blood maybe. River, our 2-year-old, gently crawled up beside me, and rubbed my head with her tiny hand. Then, without a word, she cautiously put her head on my chest and rested her arm on my stomach. Later, on the way upstairs, after we’d eaten ice cream and read books together, I heard Stella ask my wife, “Mama, is this a dream?” In her 4-year-old brain I think she had convinced herself that accident + hospital + absence = death.

I continued to have nightmares, seeing Nir’s 5 o’clock shadow and clueless expression as he stared up at me. The love I felt for our community as they rallied to support us felt incongruous with my smoldering anger, which grew hotter as each day passed. I couldn’t walk more than 20 feet without excruciating pain. The first time I tried to sit and eat dinner with my girls, I drank my water too fast and coughed and then screamed and slammed my fist on the table from a sudden shot of pain in my back. In those moments my anger towards him raged.

As the days passed and my wife continued to sponge bathe me and bring my drugs, and my girls kept easing up into my bed to read books, I softened. I didn’t have the energy or desire to pursue an international personal-injury claim. I just wanted to heal. But my wife kept saying, “Call him.” Reluctantly, I would again dial the number and get the same message. Then one morning, the screen of my phone showed an incoming call and the local number I’d been dialing relentlessly for the last week. I answered.

“Who is this?” he asked.

“The guy you were climbing with on Saturday,” I said.

There was an eerie silence, and I just knew he was going to hang up. But instead he asked how I was. Asked if I could walk. He asked if I needed anything. I told him I wanted to meet with him. He said that he was leaving the country soon to return to Israel and asked if we could meet in the next half hour.

He entered our house silently, shook my wife’s hand, and then came to the bedside and sat next to me. I didn’t speak, nor did he. It was quiet except for the plastic ticking of my back brace that came with each inhalation. He couldn’t look at my wife or me and so continued staring into his lap. My wife got him a glass of water. With great effort he looked at each of us and said he was sorry. He couldn’t speak without his eyes welling and his words becoming constricted. Eventually he explained that he wanted to pay our medical bills but that he could not do it in one payment. He would have to make several payments over the course of the next year. We decided to meet again, and then watched from the window by my bed as he crossed our street and walked toward town. Monica said, “I think he might be worse off than you.”

I called the lawyers and told them to void our contract.

A few days later Nir showed up with a contract that he had drafted and a wallet bulging with hundred-dollar bills. He had withdrawn all that he could from his bank account and was going to pay the rest in monthly installments over the next 18 months. Monica informed Nir that upon reviewing our insurance policy we had a more clear understanding of what the accident was going to cost—at least $4,000. We showed him the paperwork, and he said he could not give us what we were asking for and insisted that we accept his original offer. It was spiraling into a shrewd business deal and all of the humanity that had been infused before was leaking out. All that remained were two men negotiating soullessly. He left the room to make some calls and returned with a small concession toward our request.

“This is all I can do,” he said without looking up. “This alone is going to be very hard for me.”

“I know it will be hard,” I said, “but it’s hard not being able to be the husband I want to be, and not being able to pick up my daughters.”

Nir looked at his lap and said quietly, “My grandfather lived through three concentration camps. He lived so that I could live. I aim to live a good life. I am sorry. I will give you what you are asking for.” Then he stood and shook my hand for the last time.

Weeks went by with no word from him. Meanwhile, I practiced walking, leaning on ski poles and trying to make it to the end of our lane, but fearing that I might not be able to make it back if the pain set in too strongly. Once I had to lie down and wait for my wife to come find me. I stared up at the sky, knowing that I couldn’t move even if I wanted to. The pain was unrelenting.

The hospital bills started to flood the mailbox. Monica had embraced all possible modalities of healing by scheduling massages, acupuncture, craniosacral treatments and brain-spotting therapy sessions, as well as buying funky poultices that smelled like death. The cash that Nir had given us was long gone. I was disheartened and accepted that we might never hear from him again. A month later my wife got an e-mail from Nir with details on how to collect his first payment from Western Union.“Now where’s your faith in humanity?” she asked me.Nine months after my accident, I continued to heal. I hiked, I surfed, I meditated, I ran trails, but I could not stir the appetite for climbing. It still felt dangerous and absurd, but also as if I had lost a dear friend, or painfully fallen out of love. How could I let go of something that had given me so much?

Monica and I had proposed to one another on the top of Mount Aspiring in New Zealand after simul-climbing the Southwest Ridge. That route remains as one of the most memorable experiences in my life. We had a 24-hour high-pressure window and took off from the French Ridge Hut under a starry night to embark on 5,000 feet of climbing. We each had a small sleeping bag, two liters of water, a tube of instant coffee that came out like toothpaste, and some sliced meat and cheese, all stuffed into tiny packs that fit perfectly between our shoulder blades. We hit the ridge proper by morning and started simul-climbing up firm snow. Below us the glacier transitioned through all the hues of dawn. We moved in unison, swinging one axe, then the other, followed by two quick stabs with the front points of each crampon. We continued up through technical ice and wiggled through rotten sections that sent plates of fractured ice skating off the ridge below us. Moving nonstop, we only paused to exchange ice screws. And in those moments when we looked at each other, a softness and warmth stood in brilliant contrast to the cold, daunting reality of alpine climbing.

We summited, proposed to each other, and then traversed the ridge, eventually stumbling into a distant hut where there was only room for us to sleep under the kitchen table. We’d been climbing for 20 hours. A local who had seen us on the ridge brought us tea and said, “Good on ya,” while we lay stupefied and proud in our bags.

My fondness for the way that climbing taps into the human spirit remained. But these memories were now shadowed by fear. As a father and a husband, how could I justify returning to a sport that had come so close to taking my life?

Monica was in contact with Nir. I was not. Every once in a while she would drop one-sentence updates:

“Nir’s serving his mandatory military service as a medic.”

“Nir’s attending group counseling sessions.”

“Nir wrote to wish Stella well for her first day of kindergarten.”

Monica was also e-mailing him updates on my progress. Nir sent each payment on time, paid for the handling fees, and then sent one massive check that concluded our agreement well ahead of schedule. Monica was right. I had doubted him. When I was in the hospital I’d targeted Nir for diminishing my trust, so I was skeptical of his efforts to restore it. I’d been in therapy for getting dropped, while he was in therapy to reckon with the responsibility of dropping me. Which is worse: to fall or to watch the fall and take responsibility for it? I knew then that Nir and I would forever be tethered by the experience. It was time to write him.

Nir, you were true to your word in a manner that is rare today. I just want you to know that I harbor no resentment, mistakes happen, and we are all human. I was just worried that I might not heal, leaving my life forever altered and compromised. If my worries ever came across as resentment or anger, I would like to apologize. I am recovering each day and finding things that I can do that I couldn’t before. Somewhat like rediscovering life. This whole experience has allowed me to witness your compassion. You are an amazing person, Nir. The world is in want of more people like you.

What is climbing if not the crystallization of human trust? Trust in one’s self. Trust in others. Trust that it will work out. Nir’s integrity restored that trust.

I started to remember some of my dreams as a climber, ones that were free of the intensity that I’d been steeped in for so long: to take my girls up the Third Flatiron, to return with Monica to the Bugaboos or the Diamond for our 20th anniversary, to someday be the old guy who has found a way to maintain his love for his craft throughout the years. I could not walk away from 20 years of climbing. It had always shown me my best self. It was the solace that quieted my mind. My desire to end the “addiction” shifted to a desire to reclaim the affinity. For the purity of movement. For the totality of the experience. For the partnerships that climbing brings. Sometimes it’s not until you start eating that you realize how hungry you are.

Monica and I hatched an idea to return to Indian Creek with our girls. For 15 years I had been going to Indian Creek every fall and spring, vagabonding under the shadow of the Bridger Jack Towers. If climbing in one of the most beautiful places on earth with my wife and my girls did not spark the fire again, then it was truly over. We left Boulder and headed west despite a foreboding November forecast of high winds and rain. After an evening sitting around the fire and then sleeping in our family tent, we woke to clear skies and a low morning light that illuminated the highest escarpments in a fleeting amber glow.

We drove to Donnelly Canyon. What was once a dirt pullout, and then a small dirt lot, was now a 50-car paved lot with fresh lines of paint. We hiked to the base and the girls quickly set up shop and started rubbing colored sandstone rocks on boulders to create a fine powder, which they rubbed on their lips, cheeks and eyelids.

The spirit was slow to return. Monica encouraged me to get out of my head and to simply feel it in my body. On a tough tips lieback, I felt the joy of moving vertically surge within me. The route was at my limit and each move felt like my last. I found the tenuous balance between doubt and belief, where my body continued to prove my mind wrong. The pattern continued—doubt, belief, doubt, belief, and then I grabbed the anchor chains. I looked across the valley and then down at my girls as they scraped their rocks, their heads cocked and intent.Then I heard the sirens echoing off the canyon walls, and saw a climber running down from the Supercrack Buttress to intercept a Park Service truck. More sirens. More trucks. A crew pulled a litter out from the back of one truck and headed up the trail with it. I hiked down to see if I could help. A ranger asked if I could find the climbers who were parked in the middle of the lot because a helicopter was en route. I hiked up in search of the owners of a van with Alberta plates and a pickup with Oregon plates. When I returned to the lot, the injured climber’s wife cried out, “I feel like you are going to tell me that he is dead!” Then they brought his quiet, packaged body down the trail and loaded him on the helicopter.The helicopter lifted off and sent tumbleweeds flying. I didn’t know if he was going to live or die. A woman took the injured man’s wife in her arms. I walked slowly back up the trail to where my family was waiting, and Stella asked if she could put “makeup” on my face. I sat her on my lap, and she held the side of my head with her hand before I felt her cool index finger spreading the fine powder on my lips.“Close your eyes, Dada.”Then I felt her finger gently anointing my eyelids.

“Open.”

And there she was: my precious daughter with her radiant blue eyes so innocent of the world around us. There we were, in the desert, alive, gazing up at the autumn sky. I held her, feeling the ephemeral nature of a child’s weight.

The post The Rocky Emotional Aftermath of My Gym Climbing Accident appeared first on Climbing.